Like any farmer, Elliott Klug understands the highs and lows of living off the land. But his crop requires a rigorous effort.

Like any farmer, Elliott Klug understands the highs and lows of living off the land. But his crop requires a rigorous effort.

To keep output going, it is harvested every week. It is also grown only indoors. And though you won’t find this tip in the Farmer’s Almanac, his workers believe that blaring Grateful Dead songs boosts productivity.

“We were the bad guys,” says Mr. Klug, chief executive of Pink House Blooms, a 70-person operation that produces and sells marijuana to people who have a prescription for it. “Now we are still the bad guys, but we pay taxes.”

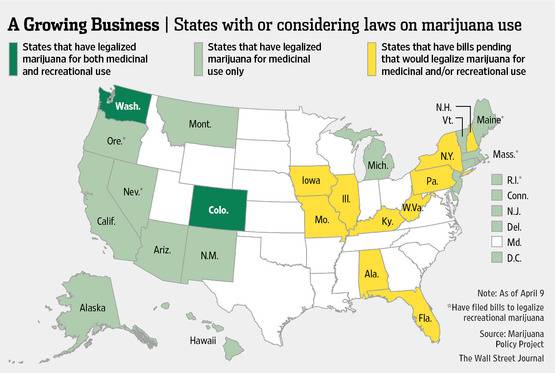

Across the country, the business of growing pot is fast becoming mainstream. Eighteen states and the District of Columbia have approved the use and production of marijuana for medicinal use, including two states, Colorado and Washington, that also allow recreational use. That has spurred on a cottage industry of professional growers, with an estimated 2,000 to 4,000 businesses now producing the plant for legal purposes. Total sales: $1.2 billion to $1.3 billion last year, according to Medical Marijuana Business Daily, an industry publication.

It’s Not Easy Growing Green

But it turns out that trying to make a profit in this business is harder than expected. When grown and sold legally, marijuana can be an expensive proposition, with high startup costs, a host of operational headaches and state regulations that a beet farmer could never imagine. In Colorado, for example, managers must submit to background checks that include revealing tattoos. The state also requires cameras in every room that has plants; Mr. Klug relies on 48 of them.

Prices for pot, meanwhile, have plummeted, in large part because of growing competition. And bank financing is out of the question: Federal law doesn’t allow these businesses, and agents sometimes raid growers even in states where it is legal.

Still, a hearty group of weed producers are coming out of the woodwork—or their basements, where they used to grow pot—to have a go at it. That includes outfits in Colorado, which hosts the first-ever High Times U.S. Cannabis Cup this weekend. The state passed a new law that next January will allow anyone 21 and older to buy marijuana from retailers, which is expected to dramatically open up a market currently limited to some 110,000 patients with prescriptions. Indeed, Medical Marijuana Business Daily forecasts a tripling in annual sales in the state in 2014 to at least $700 million.

Already, that potential growth spurt has changed the game for Mr. Klug, 36, who sports a long mustache and a dragon tattoo that stretches down one arm. Four years ago, he used to cultivate about 40 plants in his basement, as a side business while he was working in private equity. Harvests were for anyone with a prescription for pot, which included Mr. Klug, who says he uses it for pain from a gluten intolerance.

Today, Pink House Blooms is a $3 million-a-year business, with 2,000 plants in a converted warehouse in an industrial part of Denver. During a recent tour, he discusses the operation in dry business terms as his product’s distinctive scent fills the air. Stencils of marijuana leaves and a Pink Floyd poster adorn the walls. Potted plants take up almost every inch of floor space, hallways included, while workers listening to piped-in hip-hop music carefully remove stems and leaves. Their harvest is stored in a custom-made vault, with walls reinforced with three-quarter inch steel.

To get started on this scale, Mr. Klug says he sank more than $3 million—some of it borrowed from family—into the operation. He says Pink House Blooms is profitable, with demand up 30% some months. But the costs of doing business, including a $14,000-a-month electric bill, and the need to make investments to boost production, have kept him from making back any of the borrowed money. Producing marijuana on an industrial level, he says, is “exciting and exhilarating” and “in a way it’s terrifying.”

Another outfit, La Conte’s Clone Bar & Dispensary, formed a partnership with another marijuana firm to share some costs. But it produced a profit margin of only 6% on revenues of $4.2 million last year, according to Chief Financial Officer Jeremy Heidl, who says he considers that an unacceptable return given the financial and legal risks. To expand the business, the firm has branched out to sell everything from smoke-free dispensers to body salves and brownies infused with pot. Still, he says, “the economics of cannabis are so difficult.”

A major drag on earnings for marijuana growers is the labor-intensive nature of the business. Payroll can make up more than a third of production costs, says Jason Katz, chief operating officer of Local Product of Colorado. Managing workers is challenging too, he adds, in an industry where many learned their trade by growing clandestinely. His company went through six growers in three years before one worked out. “They aren’t used to being part of regular society,” he says.

Costs and management issues aside, the biggest shock to most marijuana growers has been pot prices. As the industry becomes more competitive and there is more pot available, the price for a pound of high-quality weed in Denver has slid from $2,900 at the beginning of April in 2011 to $2,400 in the same period in 2012 to $2,000 this year, according to Roberto’s MMJ List, a service that connects wholesale sellers and buyers. At the height of summer demand in 2011, a pound sold for as much as $3,900.

To be sure, some experts say it is possible to do well. Roberto Lopesino Seidita, who runs the price list and consults for the industry, says some growers are pulling in double-digit margins by focusing on price, not just quality. They have developed ways to produce large amounts of pot cheaply, and offer it at unbeatable prices, driving hundreds of customers through the door every day. “It’s run like Wal-Mart, WMT -1.35% ” he says.

Illegal growers, of course, have been producing and marketing large quantities of marijuana—often at a sizable profit—for decades. Most of the pot consumed in the U.S. is grown outdoors in Mexico by low-wage laborers, with no need for lights or air conditioning, says Jonathan Caulkins, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University who studies marijuana legalization. And street prices for pot in places where there is no legal outlet for it are generally higher than in regulated markets, Mr. Caulkins says.

Toni Savage Fox, a former owner of a landscaping business turned marijuana entrepreneur, doesn’t have all those advantages. She and other legal growers simulate summer in their warehouses with powerful lights that can run for more than 18 hours a day. Then they move the plants to a darker environment to encourage flowering and the formation on the surface of its buds, leaves and stems of trichomes, tiny resin-filled glands resembling sea anemone. That is where delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol or THC, the active ingredient mainly responsible for marijuana’s intoxicating effects, is concentrated.

“’The economics of cannabis are so difficult,’ says the chief financial officer of one marijuana firm. ”

As with many plants, spider mites and mildew can wipe out a marijuana crop. A single mistake in planting can also doom a harvest, or lower its quality and value.

Ms. Fox says she lost about 100 plants last year when a plan to boost weed production backfired. Ms. Fox planted about 100 seeds instead of starting new plants from female-plant cuttings, which are normally used to prevent pollination. But she overlooked one male seedling. It fertilized a roomful of plants, causing their flowers to go to seed and making them unsalable in a market where consumers demand to examine products under magnifying glasses.

“When you’re dealing with a living plant there are so many variables that can go wrong,” says Ms. Fox, who lost some $40,000 in the operation. “We’re still perfecting our growing spaces.”

Ms. Fox, who sometimes wears a golden marijuana-leaf pin on her lapel, is looking for an investor to pump $150,000 into her company, 3-D Denver’s Discreet Dispensary, to ramp up production ahead of the spike in demand she expects next year. The more than $500,000 of her own money she invested to convert a dilapidated party hall into a marijuana factory wasn’t enough to set up a reliable production line, she says. Setting up growing spaces costs at least $100 a square foot, and often twice that, industry experts say.

Though rarely in Colorado, federal agents still raid growers regardless of state laws when the businesses are too close to schools or lax in other ways. Last December, President Barack Obama said his administration had “bigger fish to fry” than going after recreational users. A spokeswoman for the U.S. Department of Justice said the agency is reviewing the new laws in Colorado and Washington state.

There are other legal headaches. After a marijuana strain called Bio-Diesel won a quality competition in 2009, the name started appearing in dispensaries around Denver, says Ean Seeb, owner of Denver Relief, the outfit that produced the prized variety. Prices are below his, but Mr. Seeb has no way of legally challenging his competitors; the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office won’t register cannabis-related products, he says.

While copying a name is relatively easy, obtaining the most valuable pot varieties isn’t. The chances of a seed sprouting into a worthwhile plant are the same as those of winning the lottery, says Mr. Klug of Pink House Blooms. Bringing in cuttings from out-of-state is illegal, so he says his company obtained some of the 100 strains it grows from a local grower named Charles Blackton, aka “The Lemon Man,” a six-time winner of the Cannabis Cup that is held in Amsterdam.

Offering an assortment of marijuana varieties with different flavors and prices, Mr. Klug says, has been key to building a client base. In the wood-and-metal displays at one of his stores, Mr. Klug offers high-end strains such as Phantom OG for $70 a quarter ounce, and cheaper ones such as Andy’s Blue Dream, at $50 a quarter ounce.

But clever marketing can only go so far, so he continues to work on improving quality. Instead of outsourcing trimming, or the process of removing leaves and stems from harvested flowers, Pink House Blooms has in-house workers he has trained to do the job for $11 an hour and up. (He also keeps employees satisfied by selling pot at cost to those with prescriptions.) Meanwhile, he says he still can’t find a supplier to provide large amounts of high-quality dirt at wholesale prices. He pays just a little under retail to a company that won’t deliver to his warehouse—the company’s managers don’t want to be associated with a pot enterprise, he says.

His advice for anyone who wants to become rich by legally dealing pot: “Start with lots of money.”

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for more cannabis industry news!

The Pot Business Suffers Growing Pains

Article by Ana Campoy for The Wall Street Journal