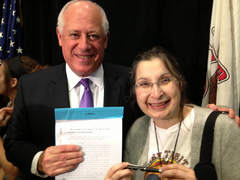

Michelle DiGiacomo, CEO of Direct Effect Charities, attended Gov. Pat Quinn’s signing of the Illinois Medical Marijuana bill at the University of Chicago Center for Care and Discovery on Aug. 1. | Direct Effect Charities photo

Marijuana was illegal in Illinois, so she always knew the day might come.

Still, when police stormed her North Side apartment a year ago, Michelle DiGiacomo was unprepared.

“I was about to experience the worst 28 hours of my life,” says the 53-year-old who runs DirectEffect Charities, a Chicago nonprofit serving needy Chicago Public Schools kids. “We had discussed this possibility in the past; one I had hoped would never come to be.”

For the past five years, the widowed mother of two had used medical marijuana for relief from the pain of fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, spinal stenosis and rotator cuff disease. Traditional medications had produced adverse reactions or failed to provide significant relief.

She was arrested Sept. 13, 2012. And on March 5 — just five months before Gov. Pat Quinn signed the state’s medical marijuana bill into law — DiGiacomo pleaded guilty to Class 4 felony possession.

Under the Illinois Compassionate Use of Medical Cannabis Pilot Program Act, a felony disqualifies a potential patient from accessing medical marijuana.

Advocates who used her story in the battle to get the bill passed say she’s an example of the new law’s deficiencies.

◆ ◆ ◆

Medical marijuana entered DiGiacomo’s life in August 2008.

Her 53-year-old husband, Paul Fitzgerald, had just been diagnosed with advanced esophageal cancer. Doctors gave him three months to live.

Doctors prescribed bottles of blue liquid morphine for his excruciating pain.

“It’s a pretty bad cancer,” says Dr. William Markey, the Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center gastroenterologist who treated him.

The morphine didn’t help.

“His pain was constant. Paul would literally get up in the middle of the night heaving from it,” DiGiacomo recalls. “Not only did morphine not work for his pain, it put his mind in a state which made it difficult to communicate. He didn’t want to spend precious time we had left together in a coma from narcotics.”

A friend who was living with HIV recommended that Fitzergald try a medical marijuana vaporizer to help increase his appetite for painful liquid feedings, DiGiacomo says.

“What eventually helped him the most was illegal. It helped ease his pain and gave him as much presence of mind as possible for the short time he had left on this earth,” DiGiacomo says.

After three months of home hospice care, her husband died on Nov. 2, 2008.

◆ ◆ ◆

Earlier that year, while the couple were on a beach vacation, DiGiacomo was hit by a five-foot wave in the ocean that tore rotator cuffs on both shoulders.

It was the beginning of learning to live with chronic pain.

“When we returned home, I began to have radiating pain throughout my body. I would see a rheumatologist who would prescribe medications that did not work and irritated my stomach greatly,” she says. “I basically learned to live in pain.”

According to Dr. Andrew Ruthberg, a Rush University Medical Center rheumatologist who has treated her for years, DiGiacomo has “several chronically painful conditions,” including “rheumatoid arthritis, a cervical spine disorder — which has required surgical repair — rotator cuff disease involving both shoulders, and a more recent lower back pain disorder.” He adds that DiGiacomo has “had difficulty tolerating many traditional medications, and I fully believe that [her] use of marijuana has been solely for the purpose of trying to moderate chronic pain.”

Her pain was so bad that DiGiacomo says she could barely walk. “I literally thought I was dying,” she says. “I’d often call my doctor begging him to help. . . . He tried and tried. Nothing he gave me would work. Or it would work for a short period of time and stop.”

The following year, DiGiacomo was diagnosed with fibromyalgia syndrome, a musculoskeletal condition characterized by chronic widespread muscle and joint pain. And a year after that, with lumbar spine disease and cervical spinal stenosis. She underwent spinal fusion surgery, which placed a plate in her neck and four screws in her spine — leading to even more pain.

Dr. Howard An is Rush University Medical Center’s director of spine surgery. He has treated DiGiacomo since September 2010, and says the surgery was critical.

“I performed a cervical spine fusion on Oct. 14, 2010, which was an urgent matter, due to her alarming spine condition,” An says. “This surgery was very risky and delicate. Pain is a daily issue living with these conditions. I know that [she has] tried numerous traditional medications without any relief. I fully believe that . . . use of marijuana has been for the use of controlling . . . chronic pain.”

In December 2009, DiGiacomo traveled to California, where medical marijuana was legal, obtained a license to purchase it and began using it in Illinois.

That mean living with both pain and fear.

“I made the difficult choice to use medical marijuana even though it was illegal, and I always felt like a criminal,” she says. “I did not want to get my medication on the street, so I made the hard decision to purchase it from a medical dispensary in California and receive it in the mail. It was terrifying. It was a horrible way to live.”

◆ ◆ ◆

On Sept. 13, 2012, DiGiacomo received by mail 670 grams of marijuana from California.

Minutes later, police were at the door.

“I opened up to multiple guns pointed at me. A police officer screamed, ‘Who’s in here?’ I told him, ‘Myself and my 14-year-old daughter.’ He asked where the guns were. I told him I had no guns. He asked where the drugs were. I told him where the small amount of medical marijuana I had in the house was, as well as what had just arrived.”

A police search of boxes addressed to DirectEffect Charities that filled her apartment turned up only school supplies that flow in during an annual back-to-school drive.

At Christmas, the 11-year-old charity collects CPS students’ letters to Santa and distributes them to donors, who answered 10,000 letters last year.

“We create programs to help children via ‘hands-on’ donors. People are able to ‘directly effect’ lives as they purchase items which we pass on to children in need. There is no middle man . . . ” she says. “I became completely disabled, but continued the charity work I had always done — from a La-Z-Boy chair in my living room.”

Her donors are like family. Many have supported the charity’s work since its inception.

“Michelle DiGiacomo is not a criminal,” says Spencer Tweedy, whose father, Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy, and mother, Susan Miller Tweedy, are longtime supporters. Spencer Tweedy helped raise $3,000 toward DiGiacomo’s legal fees.

“This is a woman who despite her numerous and severe ailments has dedicated her life to charity work. When [the police] impounded her car, it was filled with school supplies headed for impoverished students,” Tweedy said. “The cost of defending herself against the law has crippled her more than her diseases ever have.”

DiGiacomo spent the night in Cook County Jail. “It was the most degrading experience of my life,” she says.

For six months, she fought to avoid a felony conviction that could severely impact her work as CEO of a nonprofit.

The Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office would not negotiate, refusing to drop the charges from a felony to a misdemeanor, or to grant DiGiacomo a 410 probation — which allows for expungement for first-time drug offenders.

“It’s the only felony that can be expunged,” says her attorney, Michael Rediger.

“I was really surprised. The state’s attorney refused to even look at the fact that her doctors verified she was taking this as part of a medical treatment for pain, and that she did in fact have a California medicinal marijuana license; or to consider her longtime charitable work and the fact that she’d never been convicted of any other crime, not even a misdemeanor, nothing,” Rediger said.

Unable to afford trial, DiGiacomo pleaded guilty to Class 4 felony possession of cannabis. She received a year of probation.

◆ ◆ ◆

She went public.

“I first shared the experience with my charity’s donors, asking them to call their local representatives and urge them to support” the medical marijuana bill, she says. She contacted advocates and legislators.

Groups long lobbying for a medical marijuana law added hers to the cacophony of stories used to exemplify the need for the law.

“Ms. DiGiacomo’s story . . . highlighted how not having a medical cannabis law hurts good, honest, hardworking people like her,” says Dan Linn, executive director of the Illinois chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. “Each patient who helped pass this law has a story, and each of them was simply looking for compassion in the eyes of the law, not legal troubles added to the ailments they were already suffering from.”

Dan Riffle, director of federal policies for the Marijuana Policy Project, based in Washington, D.C., which pushed for the law here, agrees.

“There’s a perception that we don’t need to pass medical marijuana legislation because police wouldn’t be cruel enough to arrest a sick person just trying to ease their suffering,” Riffle said.

“Yet here’s a mother running a charity that helps thousands of kids, who was arrested at gunpoint . . . and will live the rest of her life as a felon, all because she is sick and marijuana helps her, as her doctors have attested. Stories like hers and other patients who were either arrested or lived in fear of arrest gave legislators reason to finally take action,” he said.

Now that it is legal, medical marijuana is still illegal for DiGiacomo.

The Compassionate Use of Medical Cannabis Pilot Program Act, set to take effect Jan. 1, allows patients with any of 33 “debilitating medical conditions” — DiGiacomo has four of them — 2.5 ounces of medical marijuana per two-week period.

However, it denies access for potential patients with felony convictions.

“In Illinois, individuals with criminal histories are banned from the program, and it really makes no sense,” said Chris Lindsey, legislative analyst for the Marijuana Policy Project. “I have already been in discussions with the bill sponsor . . . about fixing some of the troubling areas of the law.”

Aug. 1 was a bittersweet day, DiGiacomo says, as she sat with other patients whose stories fueled lobbying efforts, watching Quinn sign the bill into law.

“It was surreal to be with other patients who had worked for a very long time to make it happen,” she says. “While relief has finally arrived for them, it still has not for me, as my conviction will prevent me from getting the medicine that helps me the most. In light of the bill, it is my greatest hope that it will be expunged.”

Widow Who Pushed for Medical Marijuana Law Not Allowed to Use It

Article by Maudlyne Ihejirika for the Chicago Sun-Times